The fate of U.S. crude production is a big deal for the transportation industry, not just because it affects fuel costs, but because it’s such an important driver of demand.

U.S. crude output buoys ocean-going tanker rates; fills rail cars with oil and frac sand; and proffers trucker loads of equipment, water, frac sand, and oil.

Transportation feels the pain whenever drilling output stumbles. Two recent examples: the closure of Dallas-based trucking company Stevens Tanker Division due to a reduction in frac-sand demand and reports by Commtrex that railcar storage hasn’t been this lofty since 2016, courtesy of a slump in dry bulk demand and “big downturns” for frac sand.

In terms of what’s next for U.S. crude production, the best bellwether to watch may not be American consumer and industrial demand, as it has been in the past. It could be what’s happening overseas.

Incremental U.S. production is increasingly being sold to buyers in Asia, Europe, and South America. Consequently, transportation players, regardless of mode, should more closely watch developments involving U.S Gulf Coast pipelines, terminals, and tanker trades – as opposed to what’s going on at the local pump.

Major changes in U.S. exports vs. production balance

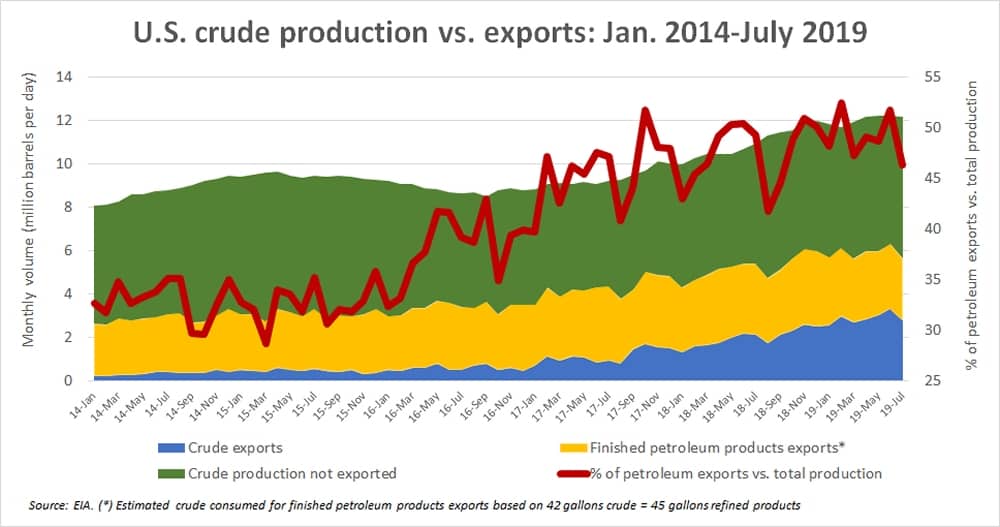

Data from the Energy Information Administration (EIA) reveals a stark change in the balance between U.S. production and exports over a relatively short period of time.

The U.S. was producing around 8 million barrels/day (b/d) of crude in early 2014. Exports of crude at that time were minimal – it was illegal to ship crude to any country but Canada until December 2015 – and the U.S. was refining about 2.5 million b/d of crude into finished products for export (using the EIA rule of thumb that 45 gallons of products are generated by a 42-gallon barrel of crude). In other words, the equivalent of around a third of U.S. production was finding its way overseas.

Flash forward to today. Production has increased by 4 million b/d or 50% to around 12 million b/d. Exports of crude oil are hovering around 3 million b/d, with finished products exports at roughly the same level, for a total of 6 million b/d of exports, equivalent to half of production.

To put it another way, of the incremental 4 million b/d of U.S. production added since early 2014, around 3.5 million b/d or 88% of that total is going overseas.

While it’s more complicated than that (because some crude imports are refined into exports and stockpiles are involved), it’s clear from a “back of the envelope” perspective that most of the newly drilled U.S. crude (or the equivalent volume) is now effectively flowing to international buyers.

Overcoming the infrastructure hurdles

The issues to watch in the oceangoing market are detailed in a new report published on Oct. 8 by Jon Chappell, the shipping analyst at Evercore ISI. “The lifting of the ban on U.S. crude oil exports in late 2015 coupled with the breakneck pace of production growth from U.S.-based shale formations is leading to tectonic shifts in the traditional crude oil trades, with longer-haul U.S. volumes more than offsetting cuts from the Middle East,” affirmed Chappell.

“Moreover, with diversity of oil supply becoming increasingly vital, especially as geopolitical risks rise – [for example] Saudi infrastructure attacks – the U.S. is becoming a more important source of secure supply globally,” he added.

Three potential hurdles stand in the way of substantial rises in U.S. crude exports: pricing conditions and issues in fields that curtail the profitability of incremental U.S. production – an increasingly pressing concern; pipeline constraints that crimp volumes from the hinterland to the coast; and suboptimal coastal facilities for tanker loadings.

Chappell believes pipeline and port issues are in the process of being resolved, which could open the floodgates to huge increases in U.S. crude export volumes in the years ahead. He believes the U.S. export trend “is likely only in the very early stages as U.S. infrastructure – in the form of pipelines and ports – de-bottlenecks some of the current constraints on getting U.S. oil to the market.”

Pipeline limitations are clearing up at this very moment, with the new 600,000 b/d Epic pipeline now flowing and the 670,000 b/d Cactus II pipeline partially open. The 900,000 b/d Gray Oak pipeline is set to come online in the fourth quarter and at least another 1.45 million b/d in pipeline capacity is slated for early 2021.

The end of the pipeline bottleneck will switch the focus toward improving tanker loading facilities. Chappell told FreightWaves, “The pipeline constraint, which had been the issue, is being addressed. Now the constraint will shift to port infrastructure.”

The problem with U.S. Gulf ports is that with one exception (the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port, or LOOP, which is primarily focused on import contracts), tanker terminals cannot handle direct calls by very large crude carriers (VLCCs). VLCCs have capacity to carry 2 million barrels of crude each and make the most sense from a voyage-economics perspective for long-haul U.S.-Asia crude transport.

Due to water-depth limitations, U.S. exporters must first load the crude aboard smaller Aframax tankers (with capacity to carry 750,000 barrels of crude) and then conduct ship-to-ship transfers with a VLCC in the Gulf of Mexico. That process can add two to three days to the voyage time and $1 million in extra expenses, which can reduce arbitrage trading opportunities and consequently pare export volumes (versus what they would have been with direct VLCC loadings).

Chappell told FreightWaves, “There are now nine [VLCC-capable] port projects that have been proposed. We doubt that even half of those will get approved or move forward, but it would only take one to two new ports to bring U.S. [crude] export potential to the 6-7 million b/d range.”

If that happens, an even greater percentage of U.S. crude production should find its way to other countries, and U.S. shale-oil drillers – as well as the trucking and rail companies that serve them – would be even more beholden to overseas, not domestic, buyers.